Text by Avani Ashtekar

‹ Return to Text by Avani Ashtekar

Labour, Re-presentation, Sharing: The Grunwick Strike

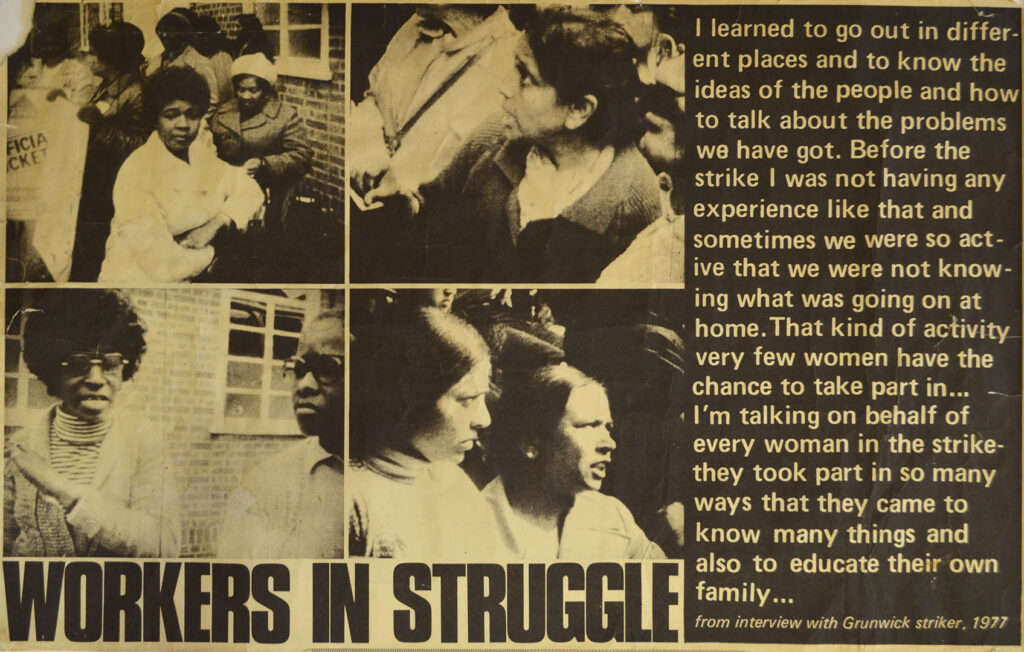

In 1976 at a film-processing laboratory in the north of London, immigrant women from Uganda, predominantly of South Asian origin dropped their tools, walked out of the labs, and went on strike. They were, of course, striking for better working conditions and better pay. But this poster reveals another aspect relevant to striking: that of re-presentation. Perhaps, it demands that we ask: how are strikes (and by proxy, strikers) represented and thus remembered? And how do they allow us to envision worker or even civil disobedience differently?

An extensive powerful photo essay on the Grunwick Strike by the Guardian, which also ironically issued apologia to Grunwick and its chairman in its text, is tagged with the headline “Strikers in Saris.” It features amongst others, Jayaben Desai, in a saree. This is perhaps the most popular formulation that memorialises that strike. With sarees being understood as a descriptor for women of South Asian origin, the headline relies on a set of equalisations: of sarees and South Asianness, but also of the Grunwick strike as by and for South Asian women. In contrast, this poster neither depicts women only in sarees nor does it delimit the strike to be a solely ‘South Asian women’s strike.’

This poster captures fleeting moments: pickets, women in conversation, discussion, and practising acts of subversion in collectivity. It tersely upends the ‘strikes in saris’ representation that dotted the newspapers in the late 1970s; images that continue to be a source of remembering the strike. Rather, it seems to be interested in highlighting, if only subtly, intersections of struggles – of classism, casteism, racism, and sexism – on whose crossroads the strike action was enacted. It does so by refusing to reproduce essentialist representations of the strikers. Instead, the four grid sections with images of always more than one striker in some form of interaction with one another are attentive to dialogue and solidarity between brown and Black feminists.

For one, it brings to mind what Audre Lorde, a Black, lesbian feminist words as “what is most important to me must be spoken, made verbal and shared…” If taken in its dual sense, sharing is an act of expressing something to someone and also of giving a part or portion of something to someone. The images in the poster set out a re-presentation of such sharing – one that is at the intersections of expressing and giving solidarity beyond identitarian essentialisms.

The quote accompanying the images, in its seamless use of collective and singular subjects “i” and “we” tells a similar story. It focuses on the re-presentation of the collective rather than the individual, and of solidarity rather than performativity. And yet, the ‘we’ is not defined. It remains in flux, perhaps always expansive. The striker’s observation that women “took part in so many ways” also makes striking a creative process. If to strike is to refuse exploitation and violence, one is compelled to ask about the different ways in which refusal is expressed. Amongst infinite possibilities of enacting refusal and solidarity, the quote leaves us with one possible way: the alteration of social relations on which organising relies i.e. the strikers “not knowing what was going on at home.” This, I think, ties together how the home and the factory are both sites of exploitation, and refusal of labouring in one necessarily upends power in the other.