New Beginnings

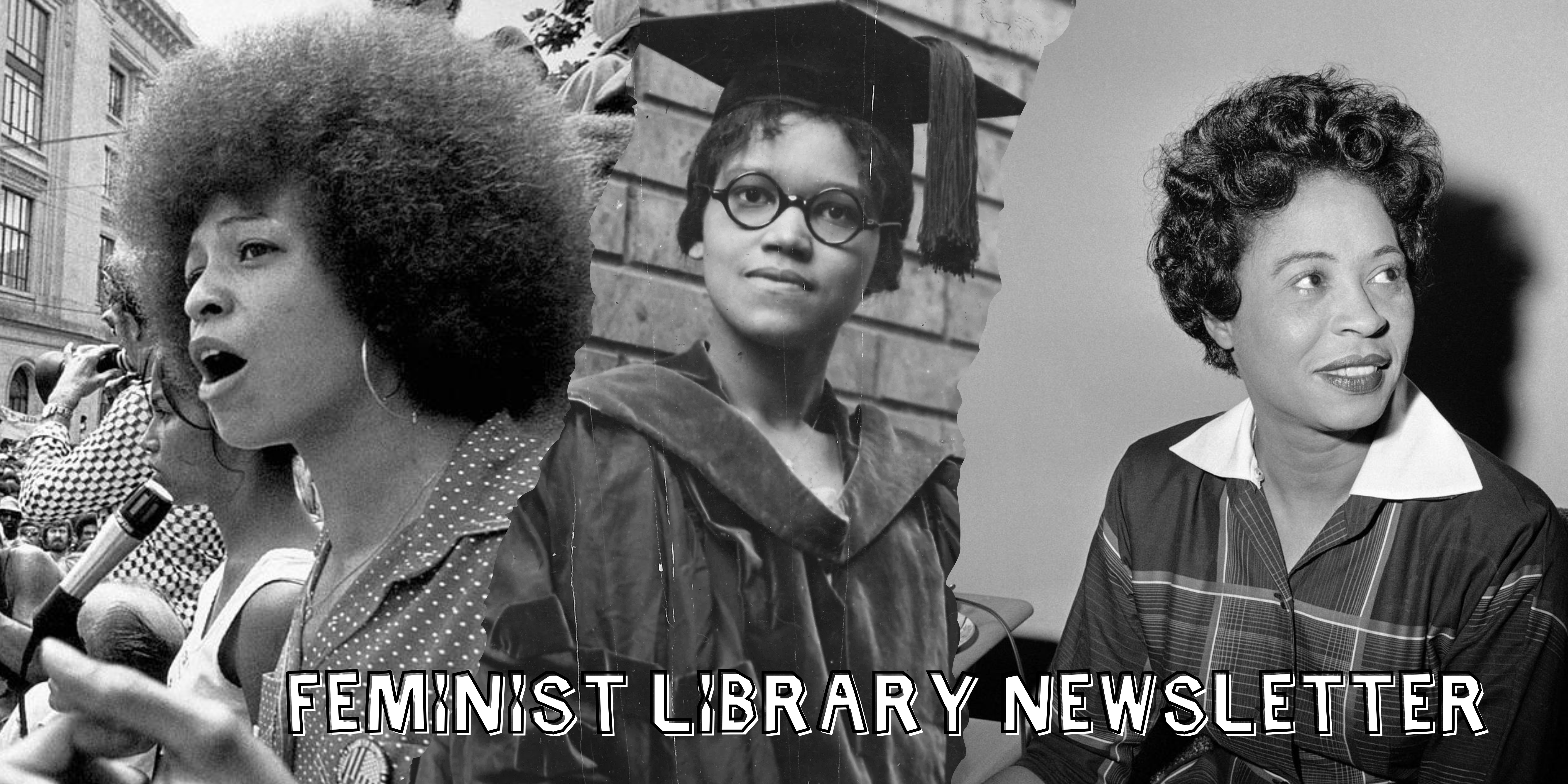

Women in history: a new column by Dami Adedoyin-Adeniyi highlighting revolutionary women of the past.

Happy new year!

January is the month for new beginnings, to make new resolutions and decide who you want to be for the next year. For example, in January 1935, Amelia Earhart made the first solo flight from Hawaii to North America. In January 1890, Nellie Bly proved that a person could circumvent the globe in less than 80 days (she did it in 72 days, 6 hours, 11 minutes and 14 seconds). January is a time to make changes in ways many people wouldn’t have thought possible, and what better way to celebrate this month than by highlighting three women who made changes people didn’t otherwise think possible.

An excellent woman who made waves previously unthinkable, is none other than Sadie Alexander. On January 2nd 1898 in Philadelphia Sadie Tanner Mossell was born to Aaron Albert Mosselll II and Mary Louisa Tanner. Throughout the course of her life she made many great changes, including to help craft the state civil rights act. However, one could argue that some of her greatest achievements started long before she began working with the law.

In 1921, she became the first African American woman to receive a Phd from an American university. This phenomenal achievement is compounded by the fact that as black woman her road to success was inhibited even further by both her race and gender. Mossell dealt with both false accusations of plagiarism and theft of her intellectual property during her time as a student, making her educational achievements even more noteworthy.

In 1923, she married Raymond Pace Alexander, at the time she received job offers from several Black colleges and universities but none of them were located in her home of Philadelphia so she stayed home for a year and did volunteer work. Fortunately, this is not where her story ends. Eventually she entered law school and became the first African American woman admitted to the University of Pennsylvania Law School. She also became the first African American woman to be admitted to the Pennsylvania Bar. Upon admission to the bar she joined her husband’s law practice as partner, specialising in state and family law.

Her doctorate in economics gave her a unique perspective throughout her life. In 1930, she published an article in the Urban League’s Opportunity magazine called ‘Negro Women in Our Economic Life’, which advocated for black women’s employment. This article was significant as it helped to highlight the uneven benefits of the New Deal. A series of domestic programs, public projects and financial reforms which aimed to address the problems caused by the Great Depression. Alexander highlighted how the New Deal did not do enough to help black people who were most hurt by the great depression, she focused on advocating for reforms to ensure that African American workers received equitable benefits from government legislation.

Eventually she was appointed to Truman’s Presidential Committee on Human Rights and her desire to help those less fortunate widened. Her advocacy primarily focused on economic issues affecting Black workers and challenging structural impediments to African American rights. In 1963 she gave a speech to the Annual Conference of Commission on Human Rights, advocating for universal employment.

While she was just one woman, Sadie Alexander set precedents previously unthought of. Not only did she break barriers once thought indestructible, but she spent her life trying to better the lives of those who couldn’t fight for themselves. Additionally, she accomplished all of this with the knowledge that every move she made would often be taken as representative not just for all black people, but for all black women. This is just a brief outline of what she accomplished in life, but even the few highlights of what she accomplished is more than enough to show how women often have to forge their own paths in a world stacked against them.

Another trailblazer who we should pay homage to this January is none other than the incredible Angela Davis.

Angela Yvonne Davis was born on January 26th 1944 in Birmingham, Alabama. The daughter of schoolteachers, Davis studied both in the US and abroad before becoming a doctoral candidate at the University of California, San Diego. She studied under the Marxist professor Herbet Marcuse. Like Alexander she did face challenges to success, her political opinions marred her excellent record as an instructor at the university’s Los Angeles campus. In 1970 she was denied the opportunity to renew her appointment as a lecturer in philosophy. However, like Alexander, Davis refused to be held back, in 1991, she became a professor in the history of consciousness at the University of California Santa Cruz and in 1995 she was appointed a presidential chair.

Despite her impressive career, what Davis is arguably best known for (and perhaps the work she should most be admired for) is her political activities. In the sixties and seventies, Davis was particularly known for championing the causes of black prisoners. She is perhaps most known for her involvement with the Soledad brothers, who were accused of killing a prison guard. During the trial of one of the brothers, George Jackon, in August 1970, an escape attempt was made at gunpoint and several people were killed. Davis was accused of taking part and was charged with murder. The investigation found that the guns were registered to her. Davis eventually went into hiding and was placed on the FBi’s most wanted list.

After her arrest in October 1970, she was returned to California to face charges of kidnapping, murder and conspiracy. It is suspected that due to her background, Davis was forcibly exposed to some of the worst aspects of the criminal justice system. Davis’ mother had been known for being a member of a communist-based Black civil rights organisation. In her youth, Davis compounded on these values and joined a communist youth group, as a young adult she took on a leadership role within a local chapter of the Communist Party. It was arguably this background that caused President Nixon, upon her arrest, to congratulate the FBi for capturing ‘the dangerous terrorist Angela Davis’. Furthermore during her stay in jail, the court denied her bail and the guards often kept her in solitary confinement. Claiming that her ideas were dangerous. Prior to this she had already been an advocate for prison reform, but her experience led her to develop an intimate knowledge of the unfair treatment of women throughout the prison system.

Eventually she was acquitted of all charges, but her time in prison only fuelled her passion for equality. She participated in an international speaking tour, visiting several communist countries, including Cuba, the Soviet Union and East Germany. She also founded several advocacy organisations, including the National Alliance Against Racist and Political Repression.

Her advocacy did not end at prison reform, she was also a champion for women’s rights, racial equality and the LGBTQ community, having come out in 1997 as a lesbian during an interview with Out magazine. In 1980 she even ran for US vice president on an unsuccessful Communist Party ticket.

Davis was once quoted saying “I’m no longer accepting the things I cannot change.. I’m changing the things I cannot accept.”. A simple phrase, yet it captures everything that she is. Many black women in her position would have, reasonably, not pushed as far as she did. With both racism, sexism and the harsh treatment of those who have been in the justice system working against her, Davis kept pushing. She kept fighting for what she thought was important, and she made sure her voice was heard. Davis went on to publish several influential books throughout her life, including Black Feminism: Gertrude “Ma” Rainey, Bessie Smith, and Billie Holiday (1998) and Are Prisons Obsolete? (2003).

However, no history (however brief) on women who made waves otherwise impossible would be complete without acknowledging Daisy Bates.

Bates, born November 11th 1914, was a journalist, publisher and a lecturer. All of which are great achievements in themselves, but none of them compare to the integral role she played in the Little Rock Integration Crisis of 1957. Bates, like many black women of her time, did not have the happiest start to life. When she was just three years old her mother was killed by three white men, this incident had a lifelong impact on her, leading her to dedicate her life to ending racial injustice.

When she was fifteen she met Lucius Christopher Bates, her future husband, and the two began travelling through the American South. Eventually they settled in Little Rock, Arkansas and started their own newspaper. The Arkansas Weekly was one of the only African American newspapers dedicated entirely towards the civil rights movements. Daisy Bates was not only an editor but a regular contributor of the paper.However, her impact does not stop there, Bates also worked with local Civil Rights organisations. This included her spending many years as President of the Arkansas chapter of the National Association for the Advancement of Coloured People (NAACP).

After the Supreme Court ruled segregated schools unconstitutional in 1954, Bates began trying to have black students registered in white schools, with minimal success. When the national NAACP office started to focus their attention towards Arkansas, they asked Bates to plan the strategy. She can be credited with the organisation of the Little Rock Nine. This was a group of nine African American students enrolled in Little Rock Central High School in 1957, whose ability to enter the school was initially obstructed by Orval Faubus, the Governor of Arkansas.

Her involvement in ensuring these students had the education their government promised them often left her a target for intimidation. Rocks would be thrown into her home and she received bullet shells in the mail. Yet despite the threats directed towards her, Bates never stopped fighting for what she believed to be right.

In 1968, she moved to Mitchellville, Arkansas, a majority black town that lacked proper economic resources. When Bates arrived she made it her mission to help those around her. She did this in a number of ways, one of which included establishing a self-help program. This program was responsible for new sewer systems, paved streets and even a community center.

Bates had published her memoir in 1962, entitled The Long Shadow of Little Rock. A book which was later republished and became the first reprinted edition to ever earn an American Book Award. In fact, the former First Lady, Eleanor Roosevelt wrote the introduction for this autobiography. Although, one could argue that the greatest tribute made to her would be the Daisy Bates Elementary School, opened in Little Rock to honour the amazing contributions she made to the city.

Sadie Alexander, Angela Davis and Daisy Bates show us how important it is to make yourself heard and to keep fighting for what you believe in. While the three may have very different approaches to what they do and what they were fighting for. The important thing is that they kept fighting for what was right, especially when it got hard. January is a time for new beginnings, it’s a time to rethink who we are and what message we want to send out into the world. These three women were courageous beyond any measure, but their bravery helps to shine a light on the types of lives we should want to lead.