5 Classic Intersectional Feminist Books

5 Classic Intersectional Feminist Books

by Jael de la Luz

Jael is a Volunteer Coordinator at the Feminist Library and her feminism is influenced by her experience as a Latin American woman, with strong links to Chicanx and Black feminism from the USA. She is currently looking to theorise intersectional Latin American feminism in a British context. Here she shares her favourite intersectional feminist books.

Feminism is for Everybody: Passionate Politics, bell hooks. A classic of black feminist theory. This text is composed of several very personal essays in which bell hooks makes a genealogy of the need to promote feminism, as a political practice that gives meaning, hope and resistance to each generation. It traces how the first feminist spaces emerged, how gender and women’s studies in universities were institutionalised, the importance of sorority, sexual identities and proposals for what would be an intersectional global feminism.

Feminism is for Everybody: Passionate Politics, bell hooks. A classic of black feminist theory. This text is composed of several very personal essays in which bell hooks makes a genealogy of the need to promote feminism, as a political practice that gives meaning, hope and resistance to each generation. It traces how the first feminist spaces emerged, how gender and women’s studies in universities were institutionalised, the importance of sorority, sexual identities and proposals for what would be an intersectional global feminism.

Sister, Outsider, Audre Lorde. This text is amazing! It is one of my favourites because it’s full of lessons in empowerment! When I read it, I identified with many of the issues Lorde writes about, such as the rage and silence that patriarchal culture has imposed on us, and the fear of recognising ourselves. Whether one is black, mestizo, lesbian, or deviates in any way from the dominant narratives of what is “normal”, Lorde encourages her readers to see their difference as a site for creativity which can be harnessed to destroy the house of the master (i.e. patriarchy, sexism, classism, racism, etc.).

Sister, Outsider, Audre Lorde. This text is amazing! It is one of my favourites because it’s full of lessons in empowerment! When I read it, I identified with many of the issues Lorde writes about, such as the rage and silence that patriarchal culture has imposed on us, and the fear of recognising ourselves. Whether one is black, mestizo, lesbian, or deviates in any way from the dominant narratives of what is “normal”, Lorde encourages her readers to see their difference as a site for creativity which can be harnessed to destroy the house of the master (i.e. patriarchy, sexism, classism, racism, etc.).

Women, Race & Class, Angela Davis. A classic that explores the racism, poverty and sexism endured by African-American women, which uses a history of slavery and its effects on the lives of women as a starting point, then exposes how even when black women were supposedly legally “free” they were still subject to oppression due to cultural stereotypes and social prejudice.

Women, Race & Class, Angela Davis. A classic that explores the racism, poverty and sexism endured by African-American women, which uses a history of slavery and its effects on the lives of women as a starting point, then exposes how even when black women were supposedly legally “free” they were still subject to oppression due to cultural stereotypes and social prejudice.

Borderlands/La Frontera: The New Mestiza, Gloria Anzaldúa. This book was translated from English to Spanish last year in Spain by Capitán Swing. It is a very performative book in which Anzaldúa critically reviews the construction of the border between Mexico and the United States, and its effects on the women left on the gringo side: the denied heritages of the indigenous culture and empowerment through language and sexuality. It’s a pioneering text in Chicano intersectional feminism and lesbian/queer studies. One of my favourite books!

Borderlands/La Frontera: The New Mestiza, Gloria Anzaldúa. This book was translated from English to Spanish last year in Spain by Capitán Swing. It is a very performative book in which Anzaldúa critically reviews the construction of the border between Mexico and the United States, and its effects on the women left on the gringo side: the denied heritages of the indigenous culture and empowerment through language and sexuality. It’s a pioneering text in Chicano intersectional feminism and lesbian/queer studies. One of my favourite books!

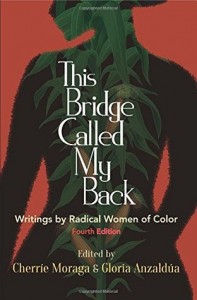

This Bridge Called My Back – Writings by Radical Women of Color, Cherríe Moraga and Ana Castillo (compilers). This book is a compilation of essays, poetry, analyses of statements and proposals for thinking about non-Western feminism within structures and territories where white privilege is normalized to exclude difference and make it invisible. It is a text which offers a range of suggestion for how one can be radical and critical.

This Bridge Called My Back – Writings by Radical Women of Color, Cherríe Moraga and Ana Castillo (compilers). This book is a compilation of essays, poetry, analyses of statements and proposals for thinking about non-Western feminism within structures and territories where white privilege is normalized to exclude difference and make it invisible. It is a text which offers a range of suggestion for how one can be radical and critical.

In the second wave of feminism, especially Western-Anglo-Saxon, white feminists spoke of all rights for all women; they talked about sisterhood between women and took to the streets to demand sexual liberation and contraceptives, they asked for the same opportunities as men in the public sphere and refused to continue to be slaves of domestic work. As good as it was that these demands were being made, women of colour (African-Americans, Chicanas, Asians, and other women with non-Western origins) were not well represented in those discourses and political practices. In the context of the feminists of the Americas, the first African-American and Chicano theorists began to question the racism that was hidden in the background of this white, middle-class intellectual feminism.

For these authors mentioned above, it was fundamental that the discourses and collective practices of feminism should include sexism within considerations of social class, skin colour and other identity-related obstacles to the full emancipation of all women, especially with regard to women with the least financial security and those excluded by political and cultural systems based on ideas of white, heterosexual and liberal supremacy.

Initially, this work was done by African-American and Chicano women within the North American context, but soon the drive for intersectionality began to gain advocates in other parts of the world, such as Great Britain, its former colonies, France and other countries of Central Europe. Thanks to theorists and activists of colour, since the end of the 1970s the general discourse of liberal and white feminism was strongly questioned, as it is to date.

Intersectional analysis is closely related to the history of African-American feminism, Diaspora movements in Central Europe, and decolonial studies. From the resistance and abolitionist movement of Sojourner Truth and the Declaration of the Collective Rio Combahee, biographies, poetry and fiction were added by women of colour who wrote in a profound way about their experiences of exclusion, sexism, poverty, criminalisation and racism. It was in the 1980s that the lawyer, activist and academic Kimberlé Williams Crenshaw formally introduced the theory of intersectionality to feminist critique. Taking into consideration the African-American reality, she spoke about how the oppression, domination and discrimination people experience are marked by identity elements such as gender, race, social class, (dis) ability, sexual orientation, religion, age, nationality, immigration status and so on. All these elements, and more, act simultaneously in how we present ourselves to the world and how others look at us, place us, stereotype us.

Some feminists encourage us to take an intersectional position because they are aware of the multiple variables that place us in spaces of exclusion or discrimination, or limited privileges, especially in migratory experiences or when our countries are historically traversed by the trauma of conquest and colonisation. From these reflections I share with you the five books above that bring us closer to black and intersectional feminist theory. They are writings that must be reread from our reality, taking into account the challenges we face today, and seeing how these proposals, theorised in the 1970s but published in the 1980s, are still valid.